Unity's scriptable render pipeline system lets us add new features to the renderer relatively painlessly. A previous article explored the basics of creating a custom RendererFeature, now let's add in a compute shader and DrawProceduralIndirect to make an exaggerated lens flare effect. We'll be working with Unity's Universal Render Pipeline (URP) and its forward renderer, although the general principles will apply elsewhere too.

Compatibility

I'm writing this using Unity 2019.3 and the URP. We'll not be using anything marked as experimental so it should continue to work in future versions. Note that the URP is designed to be compatible on a wide range of devices, but we'll be using compute shaders and some shader model 5 features which would limit our deployment targets. Take care to check compatibility especially if you want your code to work on mobile platforms.

The Plan

We're going to make an (intentionally) unrealistic type of lens flare effect. We'll let the scene get rendered as normal then find anywhere that's particularly bright and overlay a lense flare image there. Transferring data back and forth between the graphics card and general memory is pretty slow, so we want to do all that in "GPU land" which means using a compute shader and a couple of compute buffers.

- Render the scene as normal

- Find bright pixels

- Draw a lense flare on each of the bright pixels

The URP has already been made by the good people at Unity so the first step is done for us. We'll add in our work as a ScriptableRendererFeature set up to be inserted after all the other rendering is done.

Compute Shaders

As with the vertex and fragment (or pixel) shaders you may be familiar with, compute shaders are bits of code that run on the graphics card. Unlike the traditional shaders they're more general purpose, they can write to arbitrary buffers rather than being limited to vertices or fragments. In our case we'll make a compute buffer that gets filled with information about which pixels are bright. As with all shaders, graphics cards are really good at running large numbers of threads all executing the same compute shader.

// input texture

Texture2D<float3> _sourceTexture;

// a compute buffer that we can append to for output

AppendStructuredBuffer<int2> _brightPoints;The input texture is defined as it might be for any other shader. Although notice that in this case we don't need a sampler, instead we'll be able to directly access the texels using their integer coordinates.

An AppendStructuredBuffer is a dressed up compute buffer. A raw buffer would just be a an array of bytes, while a structured buffer means we can define a structure for each element in the buffer. For now that's just int2 but we could define a struct. An append buffer lets us use .Append() to add an item to the end. Importantly .Append() is a thread-safe operation. Even if we have thousands of threads all trying to add something to the buffer at the same time it'll not become a horrible mess. (A thread un-safe version might have threadA checking for an empty spot and start writing there, but at the same time threadB also thinks the spot is empty and writes in it too, causing lost or corrupt data.)

// tell Unity that the function "FindBrights" is a compute kernel

#pragma kernel FindBrights

// define thread groups for the FindBrights kernel

[numthreads(32, 32, 1)]

// these three system-value semantics let us know which thread we're in.

void FindBrights (uint3 globalId : SV_DispatchThreadID, uint3 localId : SV_GroupThreadID, uint3 groupId : SV_GroupID)

{

// access one texel from the texture

float3 colour = _sourceTexture[globalId.xy];

if (CalculateLuminance(colour) > 1.43)

{

// add our position to _brightPoints if colour is bright enough

_brightPoints.Append(int2(globalId.xy));

}

}#pragma kernel FindBrights is some of the only Unity-specific code. It lets Unity know that a function named FindBrights is a compute kernel, meaning it's something that can be used as a compute shader rather than just being a plain function.

numthreads introduces us to how compute shaders get "dispatched". Although you can run a single instance of your compute shader using a single thread, usually you'll want to run many threads at once so they can process large amounts of data in parallel (which graphics cards are very good at.) Each thread belongs to a group with numthreads defining how many threads are in each group. For convenience the group size is defined in 3 dimensions, with both [numthreads(32, 32, 1)] and [numthreads(1024, 1, 1)] creating the same number of threads. 1024 is the maximum total number of threads in a group in D3D11 (regardless of whether that's 32x32, 512x2, or 32x16x2.) There's lots of interesting optimisations to think about with group size, but as a general rule as big as possible is good. Thankfully we're not limited to processing tiny 32x32 regions. When our CPU-side code calls to dispatch a compute shader it can decide how many groups of threads to make (again defined by 3 dimensions) so we can throw millions of threads at the graphics card if needed.

Usually you'll want each thread to work on different data, in our case we want each thread to look at a different texel. We can use system-value semantics to get a thread's personal and group identity. uint3 globalId : SV_DispatchThreadID gives us a uint3 variable which is automatically filled with a thread's "position" within the whole dispatch. SV_GroupThreadID is a thread's position within its group. SV_GroupID is the index of the group itself.

Here's how those values would look for a kernel with [numthreads(3,3,1)] dispatched with DispatchCompute(..., 2, 1, 1);

SV_DispatchThreadID | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

SV_GroupThreadID | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

SV_GroupID | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

In our case we want each thread to look at a unique texel, so we'll use SV_DispatchThreadID as an index to access the input texture: float3 colour = _sourceTexture[globalId.xy]; As we want to access a specific texel we can skip the sampler middleman and directly access the data we need. That bypasses filtering, clamping, mipmaps and all that other stuff that's useful for rendering but isn't needed here.

CalculateLuminance() is a simple function to give us a luminance value from a linear sRGB colour. The only noteworthy thing here is that in HLSL (and many other, usually older, languages) functions have to be defined earlier in your source code than where they're called.

float CalculateLuminance(float3 colourLinear)

{

// magic numbers copied from wikipedia, the source of all the best magic numbers

// https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Relative_luminance

return colourLinear.x * 0.2126 +

colourLinear.y * 0.7152 +

colourLinear.z * 0.0722;

}Finally, if this thread's pixel is bright enough we add its position to the _brightPoints buffer. You'll remember from earlier that's an AppendStructuredBuffer which means our many threads can safely append to it without loss of data.

Draw Indirect

We now have a compute shader that produces a buffer with the position of every bright pixel in the rendered scene. Next we need to draw a flare for each of those. We'll use a form of DrawProcedural to do that. DrawProcedural lets us render a mesh (or in our case just a couple of triangles) without needing to provide the vertices and indices that are normally used to define a mesh. Instead we say that we want to draw a certain number of triangles and promise that the vertex shader will somehow produce the vertices needed (it's often also used with a geometry shader but we'll stick with just a vertex shader here.) In classic mesh rendering a vertex shader manipulates existing vertices, instead we'll make one that reads the data in our _brightPoints buffer and generates vertices from it.

DrawProcedural needs to know how many vertices and instances it'll be drawing. We know each flare will be drawn as a two triangle quad, but how many of those instances? That'll depend on how many bright points were found by the compute shader. That buffer's data - and its counter - only exists in GPU-land, and copying it back so we can give it to DrawProcedural isn't good for performance. Here enters DrawProceduralIndirect which works the same but instead of needing to directly tell it the triangle and instance count we can tell it what buffer to look in to find them. We can get the instance count we need into a buffer using ComputeBuffer.CopyCount or the CommandBuffer version CopyCounterValue. These copy the length of an AppendStructuredBuffer into a given location within another buffer.

Setting up a buffer to hold the draw arguments needed by DrawProceduralIndirect:

// a buffer used as draw arguments for an indirect call must be created as the IndirectArguments type.

drawArgsBuffer = new ComputeBuffer(4, sizeof(uint), ComputeBufferType.IndirectArguments);

// set this buffer up once then keep reusing it every frame with an updated instance count

drawArgsBuffer.SetData(new uint[] {

6, // vertices per instance (2 triangles of 3 vertices)

0, // instance count (will be set from brightPoints counter)

0, // byte offset of first vertex

0, // byte offset of first instance

});Within Execute of our ScriptableRenderPass:

// [after dispatching the compute shader that generates brightPoints]

// offset of 1 uint because we want to write into the instance count entry

cmd.CopyCounterValue(brightPoints, drawArgsBuffer, sizeof(uint));

// draw some number of triangles, as decided by contents of drawArgsBuffer

cmd.DrawProceduralIndirect(Matrix4x4.identity, flareMaterial, 0, MeshTopology.Triangles,

drawArgsBuffer, 0, properties);The Flare Shader

We're back to regular vertex and fragment shaders to draw each flare. The interesting part is in the vertex shader which now has to create a vertex based on our _brightPoints buffer.

StructuredBuffer<int2> _brightPoints;

// use system-value semantics to know where on the _brightPoints buffer we should read from

v2f vert (uint vertexID : SV_VertexID, uint instanceID : SV_InstanceID)

{

int2 brightPoint = _brightPoints[instanceID];

float2 pos = PositionFromBrightPoint(brightPoint, vertexID);

v2f o;

// this shader skips ztest so .z doesn't matter, so long as it's within clip space

// setting .w to 1.0 means .xyz don't get changed by the w division

o.position = float4(pos.x, pos.y, 0.5, 1.0);

// as with position's offset, vertexID tells us what uv this vertex should have

o.uv = UvFromBrightPoint(vertexID);

}First the shader needs to know where in the buffer to look. As with our compute shader we can use system-value semantics to get some information to help us. Using SV_InstanceID will give us the index of the instance that this vertex belongs to. We'll use that to look up a value from the _brightPoints buffer, meaning all 6 vertices of an instance will access the same bright position. It's no use if all those vertices end up at the same spot (the triangle would be zero size and wouldn't get rendered) so we also need SV_VertexID to identify which of the 6 vertices we're dealing with and offset it accordingly.

I'll skip listing the functions that produce position and UV values based on vertexID as there's not much to explain there. Feel free to check the full source linked below if you're interested.

An Overdraw Nightmare

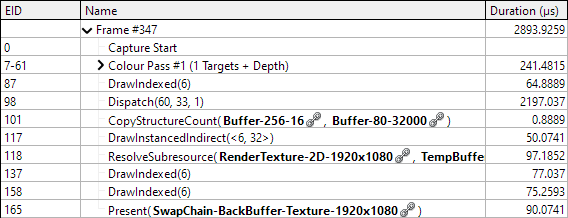

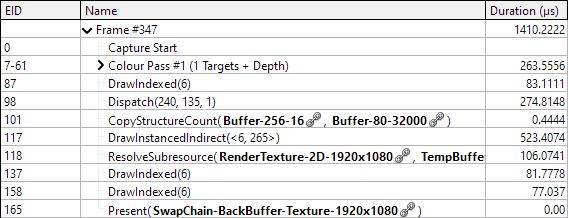

We now have something that does what we set out to do. But it seems to be causing some worrying performance problems for such a simple scene. Let's put it through RenderDoc to see what's going on.

Drawing the lens flares is taking around 98% of the total frame's render time. Oops. The problem isn't that they're complex to draw. Drawing 27k triangles isn't that much either. The problem is there's a huge amount of overlapping. Almost every pixel around the flares is maxing out the overdraw count given by RenderDoc.

This is obviously already a big problem but it could be even worse. Because we don't directly control how many flare quads are rendered or author their position it's quite possible to have very highly variable performance impact depending on the scene. In a game performance could be fine most the time but drop during brightly lit sections because the screen is suddenly full of flare quads.

Generating fewer bright spots

Compared to the 32,000µs to render the flares, our compute shader to find where they should be was a delightfully small 40µs. So we can afford to make the compute shader more complex if it cuts down on how much we need to draw. Instead of finding every bright pixel, let's chop the image up into a grid and find a maximum of one bright pixel in each cell. The thread group system used to dispatch the compute shader is already effectively splitting the image into grid cells so we can use that.

Our new compute shader needs to communicate with the other threads in its group so that together they can work out which thread has the brightest pixel and add that one to the _brightPoints buffer.

#define GROUP_SIZE 32

groupshared float cachedLuminance[GROUP_SIZE][GROUP_SIZE];

#pragma kernel FindBrights

[numthreads(GROUP_SIZE, GROUP_SIZE, 1)]

void FindBrights (uint3 globalId : SV_DispatchThreadID, uint3 localId : SV_GroupThreadID, uint3 groupId : SV_GroupID)

{

// ...

}#define lets us make a compile-time constant, which means anywhere we type GROUP_SIZE it'll automatically be replaced by whatever we define (in this case it gets replaced by 32). That's extremely useful when we want to use the same value in multiple places which may not accept a regular variable. In this case we're using it to define the 2D array cachedLuminance with dimensions that match our thread group size.

groupshared added before a variable declaration makes it shared between every thread in that group. It's not shared between all threads running this compute shader, only those in the same group. We have to be careful with shared variables. Unlike the AppendStructuredBuffer there's no automatic thread safety here, and it's easy to end up making a mess by having threads all reading and writing at the same time.

Accessing a groupshared variable is pretty fast. A common pattern is to have every thread do some texture lookup and/or calculation of a value then store it in a groupshared array that acts as a cache so the other threads that need to know about their neighbours' values don't have to calculate it themselves. There is a size limit to keep in mind, in total a compute kernel can't declare more than 32KB of groupshared data in D3D11. Our array uses 32 × 32 × 4 = 4,096 bytes so we're safe.

void FindBrights (uint3 globalId : SV_DispatchThreadID, uint3 localId : SV_GroupThreadID, uint3 groupId : SV_GroupID)

{

// every pixel gets its luminance calculated and stored

float3 colourHere = _sourceTexture[globalId.xy];

float luminanceHere = CalculateLuminance(colourHere);

cachedLuminance[localId.x][localId.y] = luminanceHere;

// wait for every thread in this group to write their values

GroupMemoryBarrier();

// ...

}As with the previous version of the shader we access one pixel on each thread and calculate its luminance. But now instead of deciding if it counts as bright, we store it in our groupshared array. We want each thread in the group to write to just one location in the array so we use SV_GroupThreadID to give each thread in the group a unique index.

The rest of the shader will rely on the data in cachedLuminance written by other threads, so before continuing we need to make sure that all the other threads have finished writing to it. GroupMemoryBarrier() achieves that by pausing this thread until all other threads in the group have completed all prior group memory activity. Often the threads in a group will be executing at exactly the same time (it's one of the ways the GPU can work so fast), but there's no guarantee of that and the exact details vary with group size and the hardware itself. You might be able to skip using GroupMemoryBarrier on your machine, but cause all kinds of difficult to reproduce errors on another.

void FindBrights (uint3 globalId : SV_DispatchThreadID, uint3 localId : SV_GroupThreadID, uint3 groupId : SV_GroupID)

{

// every pixel gets its luminance calculated and stored by one thread each

float3 colourHere = _sourceTexture[globalId.xy];

float luminanceHere = CalculateLuminance(colourHere);

cachedLuminance[localId.x][localId.y] = luminanceHere;

// wait for every thread in this group to write their values

GroupMemoryBarrier();

// All but one thread will stop here.

if (!(localId.x == 0 && localId.y == 0))

{

return;

}

// The one remaining thread finds the highest luminance in the group.

bool foundBright = false;

float brightest = _luminanceThreshold;

int2 brightestLocation;

for (int y = 0; y < GROUP_SIZE; ++y)

for (int x = 0; x < GROUP_SIZE; ++x)

{

float luminance = cachedLuminance[x][y];

if (luminance > brightest)

{

foundBright = true;

brightest = luminance;

brightestLocation = int2(x, y);

}

}

if (foundBright)

{

_brightPoints.Append(int2(

groupId.x * GROUP_SIZE + brightestLocation.x,

groupId.y * GROUP_SIZE + brightestLocation.y

));

}

}

Once we have every pixel's luminance stored we'll have just one thread look through them all and pick the brightest. So we check localId and have all but one thread return;. Stopping most threads but leaving one running is generally not a great thing to do. The way GPUs work mean the other threads can't be used to do anything else and are going to be wasted while the one remaining thread continues its work. In this case it'll not be a significant performance problem, but adopting a more parallel-friendly algorithm would be a good optimisation.

The process of finding the brightest is straightforward. The single remaining thread iterates through every item in cachedLuminance and keeps track of the highest value. If we do find a sufficiently bright pixel its position is reconstructed and it's added to the same _brightPoints buffer as before.

The rest of the process remains the same but now there's far fewer bright points generated. Sure enough drawing is much faster and our compute shader is significantly slower than before. The overall performance is greatly improved though, with total frame time around 8% of previously.

Optimisation Tweaking

Earlier we talked about how thread group size can affect performance. In this case reducing the group size to 8x8 (and increasing the number of groups dispatched so it still covers the whole image) causes a significant increase in speed on my machine. Even though we end up drawing more flares the total frame time is about 50% of what it was with the 32 group size.

I've identified two possible causes for this improvement. The flaw in our compute kernel is that in each group of threads all but one is wasted for a significant time. In an 8×8 group that means 1 in 64 threads are usefully active for the kernel's duration, in the 32×32 groups just 1 in 1024 threads are. So in the larger group more of the GPU's resources are being wasted by our non-optimal algorithm design. (Note that this reasoning falls apart in scenarios where the 8×8 group performs less work than the 32×32 group - the real solution here is improving the algorithm.)

The second possible cause is more hardware specific. I'm using an AMD card which has a 64-wide "wavefront." In overly simplistic terms that means threads are generated and run together in groups of 64. So using a group size of 64 (8×8) lets the whole group run together without being split up. The threads in a wavefront progress through the instructions at exactly the same time. Once we have enough threads in a group to need more than one wavefront some of the wavefronts will have to actually stop at our GroupMemoryBarrier().

Some more testing supports the theory that there's something special about going past 8×8 for this graphics card:

| GROUP_SIZE | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threads per Group | 36 | 49 | 64 | 81 | 100 | 121 | 144 |

| Duration (µs) | 274 | 270 | 274 | 502 | 504 | 520 | 521 |

Keep in mind that many cards aren't AMD and will have different results (an Nvidia card's equivalent property is 32.) This kind of tuning can be highly platform specific so be cautious. Also avoid blindly following rules about performance like this one. Computers are complex and there's always a lot of factors involved, so do your own experiments with your own rendering system. If you want the performance gain to work across multiple machines you'll also need to do the testing across multiple machines.

The usual optimisation warnings apply. Don't spend time chasing after magic tuning numbers on a system that isn't final yet. Check that the possible improvement would be meaningful to overall performance. Getting from 0.30% of frame time to 0.26% is neat but there's probably other places that would show more benefit from your work.

For a closer look at measuring performance and improving this algorithm, see this follow-up article.

Further Considerations

We've barely mentioned what the rest of the rendering system is doing, which is by design. The aim is our lens flare effect should be able to sit on top of whatever rendering is going on, so long as it provides an image we can feed to the compute shader. But there are a couple of things about that image we need to handle.

HDR helps a lot with finding the bright points that we want to higlight with flares. We don't need to make any special adaptations in code to handle its presence or absence, but would generally need to set a lower threshold for a pixel to count as being bright if we're not using HDR. Like the often overused bloom effects in older games without HDR support the flares will have a tendency to appear in areas which aren't bright enough to warrant the effect.

The luminance calculation assumes the colour value is in linear colour space. We could check that and swap it out for a more accurate version, but the difference is fairly minor. Our render feature being fed non-linear colours means the rendering system likely isn't handling gamma correctly in general, so one more minor colour error isn't going to have much impact.

MSAA does need some special handling. When a scene is being rendered with MSAA active we can't read from the render target in the normal way as it'll be made up of multiple samples. When MSAA is detected we can resolve the texture to a temporary render texture, then feed that to the bright detection compute shader. In theory Unity should detect that and do it for us but I encountered odd behaviour where some texture seemed to get reused from the previous frame without clearing, creating artefacts. The flares we draw don't benefit from MSAA (there's no visible mesh edges) so ideally we'd draw them into the resolved buffer and use that for the final output. Unfortunately I don't think we can tell the URP to directly use something else as the buffer to present. So we end up resolving once more than is necessary, a loss of around 80µs per frame.

Finished

There's plenty more code in the finished project which isn't explored in detail here. I wanted to focus on the core use of a compute shader to generate a buffer that's then used to render out results. I also added a couple of features to the flares. The luminance and colour of the pixel is recorded along with its position, and used to adjust the flare graphic slightly. I also added a bouncy rotation effect to the flares because it looks fun.

The example project can be downloaded directly as a .zip, or on GitHub. The code is fairly heavily commented although does assume some prior knowledge. As usual with Unity projects you'll need to do a little ritual after downloading. When you first open the project it'll take a few minutes to build the local library. You'll then need to Open Scene to open the actual sample scene in the project (Unity silently generates a default start scene and shows you that instead.) To be safe you should then restart Unity as some assets don't seem to deserialize completely at first.